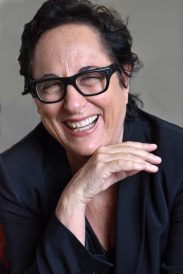

By Leslie Cohen

Special to Lesbian.com

THE AUDACITY OF A KISS: Love, Art, and Liberation by Leslie Cohen (Rutgers University Press) tells the story of Leslie Cohen and her partner Beth Suskin who served as models for the iconic sculpture “Gay Liberation” in Greenwich Village. In this evocative memoir, Cohen tells the story of a love that has lasted for over fifty years and recounts her quest to build gay and feminist oases in New York, including the groundbreaking women’s nightclub Sahara. Please enjoy an excerpt from her memoir.

Prologue

In 1979, George Segal, the famous Pop artist, was commissioned to create a sculpture commemorating the 1969 Stonewall uprising in New York City. The uprising was the seminal, although not the only, event to kick-start the gay liberation movement. Segal’s bronze sculpture, covered with a white lacquer finish, was eventually unveiled in Christopher Park in Greenwich Village, formerly known as Sheridan Square Park, in 1992, after almost thirteen years of controversy. The sculpture is called Gay Liberation. It depicts a life-size male couple standing a few feet away from a life-size female couple sitting together on a park bench. One of the men holds the shoulder of his friend. One of the women touches the thigh of her partner as they gaze into each other’s eyes. Over the years, Gay Liberation, the sculpture, has become more and more recognizable around the world and an icon that is visited by thousands of people every year.

Beth Suskin, my partner (and now wife) of more than forty- five years, and I were the models for this sculpture. Since the sculpture’s unveiling in 1992, we have stood before it many times, staring at our doppelganger selves. We have witnessed drunken men slouched on the park bench with their heads resting on our laps, children climbing on us like monkey bars and sitting on our knees, and grown men and women crying openly before it, overcome with emotion, because they remember the many years of humiliation they experienced when they were taunted, arrested, and forced to hide because they were gay or lesbian. Gay men and lesbians from around the world have come to see the sculpture as a symbol of gay pride and as a confirmation of the great progress that has been made towards their visibility and acceptance.

It is astounding to us that our love for one another is publicly signified and immortalized in this way. However, our love story cannot be told in full without also including the tale of Sahara, the first New York City nightclub owned by women and designed for women. I opened it with three other women in Manhattan in 1976. The club was an elegant oasis in a desert of oppression against women, both gay and straight, where women discovered a safe space to express who they were. Luminaries of the time came to wit- ness and bask in the welcoming scene, which in turn nurtured a generation of women who would become luminaries of the future. Beth and I discovered our love for each other and nurtured it against the backdrop of Sahara, and in my mind, they are inextricably woven together. This is our story.

Secrets and Dreams

I was born in 1947, two years after the Hiroshima bomb and the end of World War II, the year that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was formed. Jackie Robinson became the first African American to play baseball for a major league team, and the gender- bending artist, David Bowie, was born. Whatever memories I have of my earliest years are few but sweet. I played, I laughed, I skinned my knees. When I was four or five years old, I stared up at the sky one afternoon trying to see God. What appeared overhead was the enormous image of the Knickerbocker man (an image from an old beer ad of the time) in his colonial dress and three-cornered hat looming over me amongst the clouds. This appearance of what I thought was God was so real that it frightened me, and I ran into the house to find my mother.

In 1955, for my eighth birthday, my mother, Marcia, gave me a pink bassinet stroller. Curious, I peeked under the hood of this alien girl’s toy to find a plastic doll wrapped in a blanket. I smiled and thanked my mother, not knowing what I would ever do with this oversized plaything in which I had absolutely no interest. I decided that the carriage could be useful to store my catcher’s mitt, base- ball, and bat when I wasn’t using them. They would be safe there next to the doll that I never touched.

In the large apartment complex in Whitestone, Queens, where we lived, my play area was a paved quad, partially inhabited by a one-story parking garage and a concrete playground made up of seesaws and swings. Adjacent to the playground were rows of do- it-yourself clotheslines that sagged in the background from the weight of boxer shorts, undershirts, and bleached white bedsheets that swayed in the wind like flags of surrender. The smell of fresh detergent permeated the air around us. Corralling the quad on all sides were the indistinguishable and unadorned two-story, connected, redbrick apartment buildings. Sparse trees and grass were scattered around, but pavement underlined almost everything.

LESLIE COHEN has been a museum curator, a nightclub owner and promoter, a limousine driver, and a lawyer, as well as a writer whose work has appeared in such publications as Curve and The New York Times Style Magazine. Now retired, she and her wife Beth live in Miami, Florida with their cat, Birdie.

For more information: https://www.leslie-cohen.com