By Lee Lynch

By Lee Lynch

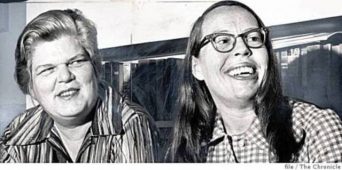

“We lost a giant today,” tweeted California State Sen. Scott Weiner, who is chairman of the LGBTQ caucus. A giant is exactly what the ninety-five-year-old Phyllis Lyon was, along with her partner Del Martin, who died at age eighty-seven in 2008.

My friend the sailor broke the news to me. She e-mailed, Del and Phyllis made a difference in my life. Yours too? No finer compliment could be given.

I responded: Oh, this hurts. They certainly made a difference for me. I was able to read their creation, “The Ladder,” from age fifteen on. They were role models as a couple and in their activism. Thanks for breaking it to me.”

Yes, with my hair slicked back by my father’s Vitalis, in the hand me downs from a boy across the court, hoping to someday own a pinky ring, and waiting to reach an age when I could frequent the rough and tumble gay bars downtown, my girlfriend Suzy and I spotted the magazine founded by Phyllis and Del.

It was an unthinkable accomplishment then, the production of a periodical about ourselves. We weren’t even old enough to legally buy it. Suzy, the bolder of us, probably took it to the register anyway. Or maybe some other babydyke swiped it, afraid to take it to a cashier, and passed it on, afraid to take it home to Brooklyn or New Jersey where she lived with her parents.

If Suzy and I were afraid to purchase “The Ladder,” I cannot imagine the enormous courage of Del and Phyllis. They gathered material from closeted lesbians, signed their real names to their own writings, and, braver still, approached a printer. I remember the struggle Tee Corinne and I had twenty-five years later, getting our local copy shop to print our self-published works.

Where had this paper miracle come from? Who was behind it? I was a contributor to “The Ladder” before I knew its history. By 1960, the year I first read it, “The Ladder” was on Volume 5. It was published in San Francisco. How had it been distributed to a magazine store in New York? Of course, we were still children and adults ran the world, even our world. We might question and defy authority, but the magazine was a product of adults and whatever magic they supplied to make things work. I was in awe.

Today, “The Ladder” might look like a dinky little magazine. In 1955, when they first achieved this marvel, it must have represented a logistical obstacle course for Del and Phyllis, whose activism consisted of much more than the printed word. Like so many lesbian projects right up to the present day, the work they and their cohorts produced was all volunteer. They risked loss of their jobs, their birth families, their lovers, their homes, their very sanity, to assert the legitimacy of our condemned lives. There was nothing dinky about that magazine, or the men’s equivalent, “One.” Both periodicals were powder kegs fueling what was to become the gay rights movement, a movement that changed government, schools, religious institutions, the military, and the lives of fearful, confused, often self-hating individuals who found our way to fuller lives and healthier psyches.

Phyllis Lyon made a profound difference in my life. It was due to Phyllis that I survived my otherwise unguided, unmodeled teens. It was due to Phyllis I was able to resist the course of conversion therapy (not called that then) my college unofficially required of me. It was due to Phyllis that an outlet existed for my words. It was due to Phyllis and her union with Del that I saw I could commit to a woman I loved and stay for better or worse. It was due to the tenacity and victories of Phyllis Lyon and our other giants that I lived to embrace who I am because she so publicly embraced who she was.

So yes, my sailor friend, let’s just say she made it possible for me to be a very happy, stable, exultantly married woman and published lesbian writer today. I am one of her accomplishments. I hope she was just as proud of me as I’ve always been of her.

Copyright Lee Lynch 2020