BY FRANCESCA LEWIS

BY FRANCESCA LEWIS

Lesbian.com

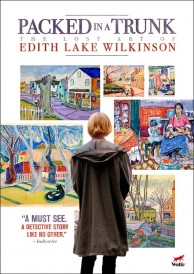

We all have that fantasy of finding a trunk of priceless family heirlooms in the attic, but in Jane Anderson’s case, such a discovery led to something a lot more fulfilling than money. Anderson, an award-winning writer/director whose most recent work Olive Kitteridge won an Emmy in 2014, has been surrounded by her Great Aunt Edith’s artwork all her life. Discovered by her mother in a bunch of old steamer trunks in the attic, they decorated the walls of her house when she was growing up. Not much was known about the mysterious Aunt Edith, except that she was born in the 1860s and spent the latter 30 years of her life in an asylum. As Anderson herself grew into a bohemian artist, living in New York, in part inspired by what she knew of her artsy Aunt Edith’s life, she became fascinated with this familial kindred spirit. Her mother would send her sketches, done by Edith when she was in New York herself, that were almost identical to the ones Anderson herself was making. Upon researching Edith’s life she learned two things – that Edith, like her, was a lesbian, spending her life with a “companion” named Fanny, and that it appeared that Edith’s incarceration was less about mental illness and more about a greedy attorney who wanted to get his mitts on her inheritance. Thus began a lifelong obsession with her aunt. Over the years Anderson tried to learn more about Edith Lake Wilkinson – her art, her life, her tragedy – and to get her recognised by the art world. Finally, reaching the same age Edith was when she was put away, happily married to her spouse Tess, she embarked upon this documentary project and her aunt’s story finally opened up in fascinating and surprising ways. The resulting film, Packed in a Trunk: The Lost Art of Edith Lake Wilkinson, is a lively, colorful film full of heart, beauty and sadness – part detective story, part history lesson, part love letter to a kindred spirit.

Probably the most wonderful thing about this film, other than the intriguing story, is Anderson herself. A bubbly character with a vibrant red bob and a selection of funky glasses, she makes this so much more entertaining than a film about a woman who was wrongly thrown into an asylum would typically be. Her relationship with Tess, who seems like the yin to her yang, a serene and centred presence, lends a sweet dimension to the film, also providing an interesting mirror to the relationship of Edith and Fanny. As is pointed out in the film, Jane and Tess have what Edith and Fanny were tragically denied: the freedom to be in love.

Packed In The Trunk would be a worthwhile film even if it focused on an untalented relative with the same backstory, but what is surprising is that Edith Lake Wilkinson’s work actually has a significant place in American art history. Edith was part of a group of modernists in Provincetown in the 1910/20s whose names are well known for their work with white line printmaking. Anderson learns in the film that there is compelling evidence, in the dating of a piece she possesses, that her Aunt originated the style. This leads to her being prominently featured in a show at the Provincetown Art Association Museum, a place Anderson had longed to see Edith’s work displayed for some time. It is the smaller show before this, however, held in a building Edith painted many years ago, where Jane and Tess lovingly decorate the walls Edith’s favourite shade of forest green, that feels like the real victory. There are a number of genuinely moving moments in this film but Anderson’s exuberance and playful humour ensures that it never becomes sentimental or maudlin.

The details of Edith’s life are never fully uncovered, but we do learn a few things. Edith Lake Wilkinson studied art, moved to New York, and later spent a lot of time in Provincetown where she was friends with prominent members of the art scene there. Provincetown was a place where bohemians and queer people could live safely – a tolerant and progressive haven. Unfortunately, it seems that all it took to doom Edith to a life of tragedy was an unscrupulous attorney, and at the age of 57, just as she planned to move to Paris to join the thriving art scene there, he had her committed to an asylum in order to steal her money. Her diagnosis: paranoia. Likely she told the staff her lawyer was robbing her blind, but this was the 1920s and nobody listened. Edith remained incarcerated until her death in the 1950s. A tragic tale indeed – an independent and talented woman, cut off in her prime – which makes her grand-niece’s crusade to have her properly recognised all the more poignant.

The details of Edith’s life are never fully uncovered, but we do learn a few things. Edith Lake Wilkinson studied art, moved to New York, and later spent a lot of time in Provincetown where she was friends with prominent members of the art scene there. Provincetown was a place where bohemians and queer people could live safely – a tolerant and progressive haven. Unfortunately, it seems that all it took to doom Edith to a life of tragedy was an unscrupulous attorney, and at the age of 57, just as she planned to move to Paris to join the thriving art scene there, he had her committed to an asylum in order to steal her money. Her diagnosis: paranoia. Likely she told the staff her lawyer was robbing her blind, but this was the 1920s and nobody listened. Edith remained incarcerated until her death in the 1950s. A tragic tale indeed – an independent and talented woman, cut off in her prime – which makes her grand-niece’s crusade to have her properly recognised all the more poignant.

Packed In The Trunk: The Lost Art of Edith Lake Wilkinson is delightful on a number of levels. Firstly, it charts Edith’s return to her proper place in American art history. Secondly, it provides a window into the life of a queer woman who lived a century ago – and into the strides society has made in the time since then. Thirdly, and for me most importantly, it is a very human, very touching story about love, passion and the ways that those who have gone before us, even if they passed before we ever lived, can still have a profound effect on our lives.

You can watch Packed In The Trunk: The Lost Art of Edith Lake Wilkinson on Wolfe video.

Francesca Lewis is a queer feminist writer from Yorkshire, UK. She has written for Curve Magazine, DIVA Magazine, xoJane and The Human Experience. You can find her opinion pieces on Medium.